AGATA SŁOWAK: Time is Love

Past exhibition

Overview

Essay by Alison M. Gingeras

“Balls to the wall” is not a colloquial phrase used in the Polish language, though the expression feels particularly apt for a discussion of painter Agata Słowak. Contemporary usages presume that the balls in question are “testicles” which are pressed—enduring this metaphoric act of torture testifies to the person’s defiance, maximalism, or extreme daring. The original coinage, pioneered by steam-engine operators in the 19th century, derived from pushing the “balls” that topped their machinery levers to the full throttle position, thus recklessly hurtling a train to top speed. Both versions of this imagistic phrase apply to Słowak who audaciously paints sexualized visual narratives—oftentimes explicitly rendering graphic scenes, male genitalia, scrotum as well as penises in full erection—with disarming, Old Master-style pictorial flair. She fearlessly careens the viewer headlong into atmospheric paintings drenched in complicated, often conflicting desires.

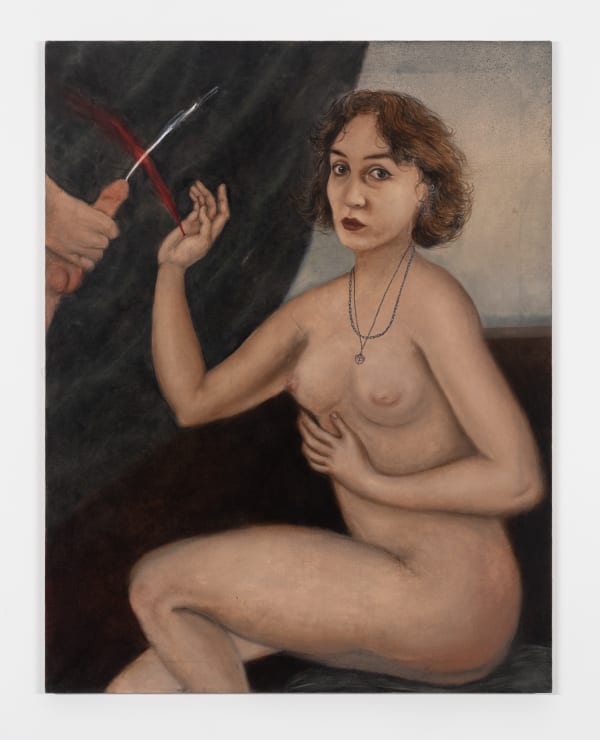

The mismatched gender of the phrase fits Słowak’s refreshing take on phallic feminism—a mantle that Słowak moves away from contentious, highly ideological sexual politics of the second wave of the 60s and 70s, into more magical realist terrain. “If the erect penis is not ‘wholesome’ enough to go into museums—it should not be considered ‘wholesome’ enough to go into women,” proclaimed artist Anita Steckel in her 1973 manifesto “Fight Censorship” “and if the erect penis is ‘wholesome’ enough to go into women, then it is more than ‘wholesome’ enough to go into the greatest art museums.” Thanks to pioneers such as Steckel, Betty Tompkins, Judith Bernstein and Joan Semmel whose work first and foremost vindicated their right to depict male nudity and explicit eroticism, Słowak inherited the legitimacy of sexual subject matter as a given. Unlike her forbearers, Słowak’s work does not portend a specific political agenda of representation as its primary raison d’être. Instead, the sexuality and occasional graphic content are a byproduct of an imaginary, often allegorical self-exploration. The artist herself often is depicted as the primary protagonist of the paintings—her likeness appears in a majority of her canvases.

Enacting a form of auto-psychoanalysis with a brush, the point of Słowak’s work is not reduceable to transgressive representation. Her struggles are more inward facing. Take for instance her most “balls to the wall” painting to date—White Balls on the Wall (2023). A woman’s hand clutches an erect penis, her dark nail polish further adorned with actual nails that pierce and enforce her fierce grip. A very slight rivulet of blood emanates from the pinkie finger that holds the phallus, drawing the viewer’s eye downward. The woman’s wrist is adorned with a cross bracelet—a nod to the artist’s rural, devout Catholic upbringing in Poland. Słowak’s literal enactment of “balls to the wall” as well as visual punning feels ripe for psychosexual riffing: is this sex act a form of Catholic sacrifice? Grasping a martyred cock, turning it into a substitute for a wounded Christ or a pierced Saint Sebastian? The penis as an extension of the Arma Christi? Could this scene enact an extreme form of self-affirmation—simultaneously avowing (hetero) sexual desires while acknowledging her penis envy—nailing herself to the subject/object of her desire while attempting to represent her phallic lack? Or perhaps Slowak has studied Leo Steinberg — whose groundbreaking study “The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art”argues that pictorial emphasis on Christ’s penis by artist’s of the 16th century was a deliberate means of emphasizing his humanity while echoing the Vatican’s theological teachings.

A second work entitled Penis Constellation (Kitty’s Paw) further pushes the conflation of Christ and cock. Inspired by a new lover, Słowak decided to portray an erect penis hooked on a fishing line—with a whole school of small minnows hooked and swimming up the legs and torso in the same direction as the penis. Playing on the Biblical story in which Jesus beseeched his disciples on the Sea of Galilee, "Follow me, and I will make you fishers of men." (Matthew 4:19) Słowak explains, “I wanted to queer Jesus, literally having him fishing for gay male followers… my lover also happens to attract men.” The disturbing presence of the black cat's paw on the man's leg is a stand in for the artist herself. While certainly indebted to the women artists who paved the way for creating such confrontationally phallic iconography, Słowak deploys this feminist license to mine the subconscious exploration of her psyche—itself a political act, especially against the backdrop of repressive policies against women and LGBTQ people passed by Poland’s extreme right-wing ruling party.

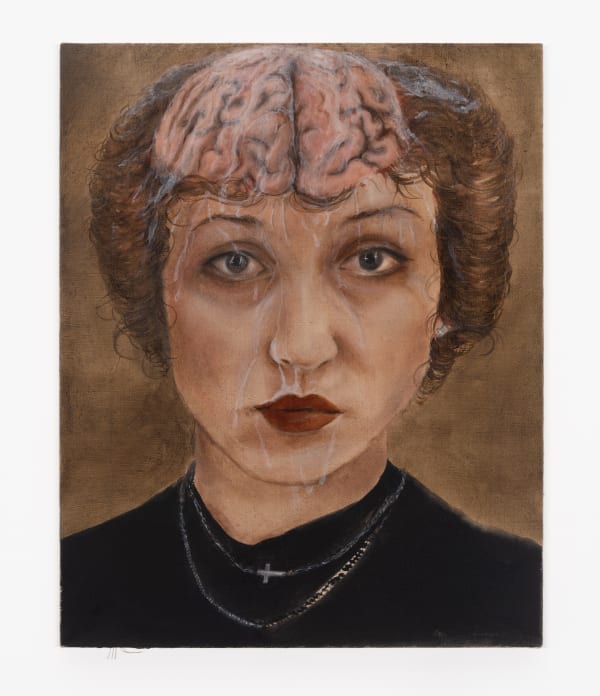

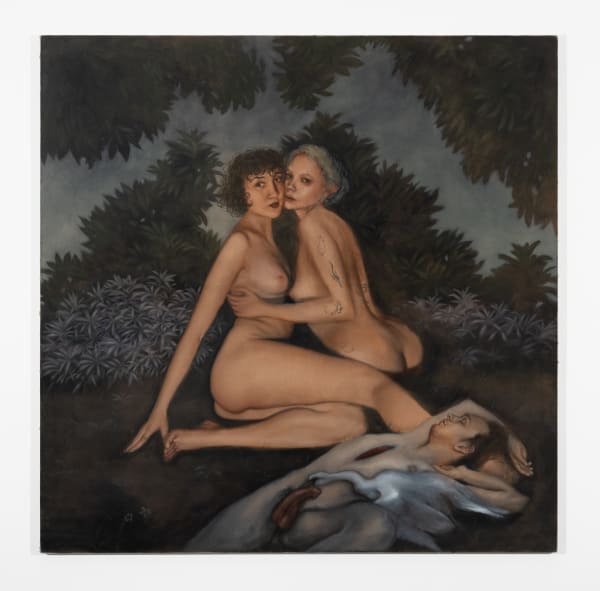

In other pictorial self-diagnoses, Słowak depicts herself literally split in two, torn apart by a fox and polar bear. Split between two lovers, a bajka* of bisexuality? On another canvas, Słowak stares blankly at the viewer, her brain protrudes from her head, exposing its literal “saturation” in sperm. Her bisexuality is further explored in erotic scenes depicting throuples. Swansong portrays a nude Słowak and her presumed female lover entwined in an amorous embrace, while a sleeping, or perhaps dead, man lies in the composition's foreground. His erection and slit-open chest are framed by the titular swan—perhaps a reference to Zeus who transformed himself into a swan to seduce and eventually rape Leda, the Spartan queen. Yet in Słowak’s retelling, the all-powerful Zeus-as-swan is sidelined as a spectator, passively left to watch the two women. The swan’s long, phallic neck is outstretched on the sleeping man, an extension of his futile erection. Słowak paints a swansong of suspended, heteronormative desires.

Like a mash-up of Leonor Fini’s erotic dreamscapes and Hannah Wilke’s performative sexuality, Słowak fashions a universe in which women are empowered, radical agents of their own desire, and men are passive, objectified, and subordinate. Seen as a whole, Słowak’s painted world is tethered to “reality”—although magical, fetishistic, and erotically tinged elements puncture the presumed normality of the everyday. In the span of a few short years since receiving her diploma at Warsaw’s Fine Art Academy in 2019, Słowak has had a meteoric rise in the Polish and international art worlds with her enchanting, yet unsettling imagery. Her idiosyncratic paintings are at the intersection of identity and eros, power and gender in an age when all of these primal forces are being fundamentally interrogated.

*Bajka is the Polish word for children’s tales, often featuring anthropomorphiciz

Works

-

Agata Słowak, Łabędzi Śpiew (Swansong), 2022

Agata Słowak, Łabędzi Śpiew (Swansong), 2022 -

Agata Słowak, Autoportret z krzyżowaniem spermy i krwi (Self-portrait with Sperm and Blood Crossing), 2023

Agata Słowak, Autoportret z krzyżowaniem spermy i krwi (Self-portrait with Sperm and Blood Crossing), 2023 -

Agata Słowak, Konstelacja penisa (łapka kotka) (Penis Constellation (kitty's paw)), 2023

Agata Słowak, Konstelacja penisa (łapka kotka) (Penis Constellation (kitty's paw)), 2023 -

Agata Słowak, Byclo Ci Zimno w Moim Cieniu (You Were Cold in My Shadow), 2023

Agata Słowak, Byclo Ci Zimno w Moim Cieniu (You Were Cold in My Shadow), 2023 -

Agata Słowak, Z Cylku (From the Cycle, White Balls on the Wall), 2023

Agata Słowak, Z Cylku (From the Cycle, White Balls on the Wall), 2023 -

Agata Słowak, Joanna ze świnka (Joanna With the Pig), 2023

Agata Słowak, Joanna ze świnka (Joanna With the Pig), 2023

Installation Views

Press

-

The Best New York Art Shows of 2023

Jerry Saltz, Vulture, December 15, 2023 -

Agata Słowak

Claire Milbrath, Editorial Magazine, October 25, 2023 -

Artist Agata Słowak about the exhibition in New York

Anna Pajecka, Vogue Poland, August 21, 2023 -

Agata Slowak’s Personal Jesus

Jerry Saltz, New York Magazine, June 21, 2023 -

Christ, Cocks, and All That Jazz

Hakim Bishara , Hyperallergic, June 12, 2023 -

Agata Słowak: Time Is Love

Hatty Nestor, Studio International, June 8, 2023